Who Shows Up, Who Decides? Delegation Size & New Dynamics of Global Health At The World Health Assembly 2025 [Guest Essay]

Newsletter Edition #276 [The Files In-Depth]

Hi,

“Presence is power. Wealth matters, but politics matters even more”: authors of today’s guest essay assert. In their refreshing and lucid analysis, global health experts Jaime Manzano Lorenzo and Adrián Alonso Ruiz from a Spanish civil society organization, have mapped delegation size and presence at the recently concluded World Health Assembly in Geneva.

They say that delegation size can be seen as a proxy for political will, technical capacity, and influence.

These experts are affiliated with Salud por Derecho, a Madrid-based civil society organization working towards affordable health technologies and reforms of pharmaceutical policies.

This highly recommended piece is great reading for anyone wishing to understand the shift underway in global health and geopolitics.

I am most grateful to these experts for making their research available to our readers. Get in touch with them with your feedback!

Find our work valuable? Consider become a paying subscriber. Tracking global health policy-making in Geneva is tough and expensive. Help us in raising important questions, and in keeping an ear to the ground. Readers paying for our work helps us meet our costs.

Our gratitude to our subscribers who ensure we are able to pursue public interest journalism.

Best,

Priti

Feel free to write to us: genevahealthfiles@gmail.com

Find us on BlueSky: https://bsky.app/profile/genevahealthfiles.bsky.social

I. WHA78: ANALYSIS

Who Shows Up, Who Decides? Delegation Size & New Dynamics of Global Health At The World Health Assembly 2025

By Jaime Manzano Lorenzo and Adrián Alonso Ruiz from Salud por Derecho

Salud por Derecho is a Madrid-based civil society organization working to ensure universal access to affordable health technologies and to reform pharmaceutical policies globally.

Get in touch with the authors here: jaime.manzano@saludporderecho.org.

Geneva – the capital of global health diplomacy becomes a hive of activity every year in May during the World Health Assembly. The WHA convenes member states to discuss the organization’s policy priorities and budget, approves resolutions that build on norms, issue recommendations, reports and even votes on contentious political matters that underpin health.

This WHA was special, considering the adoption of a resolution to approve the final text of the Pandemic Treaty ( the treaty will enter into force later and is not yet open for signatures). In addition, the budget cuts due to the US withdrawal from WHO, and a reduction in aid from many other donor countries, is causing a major earthquake in how WHO and the Global Health system as a whole operates and is financed.

In addition to the official agenda inside the Palais des Nations – the venue of the Assembly, dozens if not hundreds of meetings and side events take place on the sidelines of the official proceedings. For this 2025 World Health Assembly, we have analyzed two aspects that we think reveal some of the power dynamics operating in Geneva during WHA: delegation sizes and event hosting.

What Delegation Size Tells Us — and Why It Matters

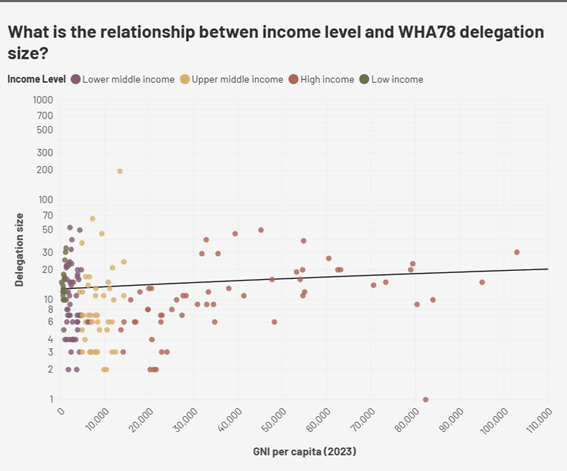

WHO’s ‘one-country-one-vote’ rule is aimed to ensure equal representation to all countries, regardless its size, wealth, or their contributions to WHO. However, not every country comes to Geneva with the same capacities. A closer look at the size and composition of national delegations reveals a different layer in global health power politics and offers insights into who is investing political capital in global health, and who is not (Figure 1).

A few key findings stood out in our analysis:

(To see the entire data-story in Flourish, click here)

This was the first Assembly since the creation of WHO in 1948 without a US delegation. The new administration’s decision to exit WHO resulted in the first ever Assembly without a US delegation. The US was the promoter of the UN-system and a hegemonic power in Global Health, through its vast technical, financial and diplomatic capacity deployed in the Global Health System.

Compared to countries from the same income group, China’s delegation this year was exceptionally large. While most upper middle-income countries sent a median of just 7 delegates, China sent 194.Despite not having a frontline role in Global Health diplomacy historically, and its tendency to operate through bilateral agreements, many claimed that US withdrawal would let space for Chinese diplomats to gain more relevance in the Global Health system. This year, China arrived in Geneva with the largest delegation, which might point towards a greater effort to influence global health. (China announced US$500 million over five years that also includes its membership dues to WHO. Countries agreed to pay more to WHO under a previously negotiated decision – a small but significant step to sustainably finance the organization. See more below.)

Wealth matters, but politics matters more.

On average, higher-income countries send larger delegations. But the biggest outliers are not just the richest, but the countries making a deliberate choice to show up in force, with delegations with expertise and a background in engaging in health diplomacy (e.g., India, Thailand, Brazil, Ethiopia or the Philippines).

Why does this matter? Because delegation size can be seen as a proxy for political will, technical capacity, and influence. Whereas the ‘one country, one vote’ is an example of how rules can be wielded to grant equal decision-making powers to all country delegations, larger delegations can attend simultaneous sessions, they can negotiate amendments and build coalitions, participate in more informal negotiations, and host or join more side events. Presence is power, and it also shows a country’s capacity to draw from the different departments involved in the negotiations (from health ministries, to science, or foreign affairs).

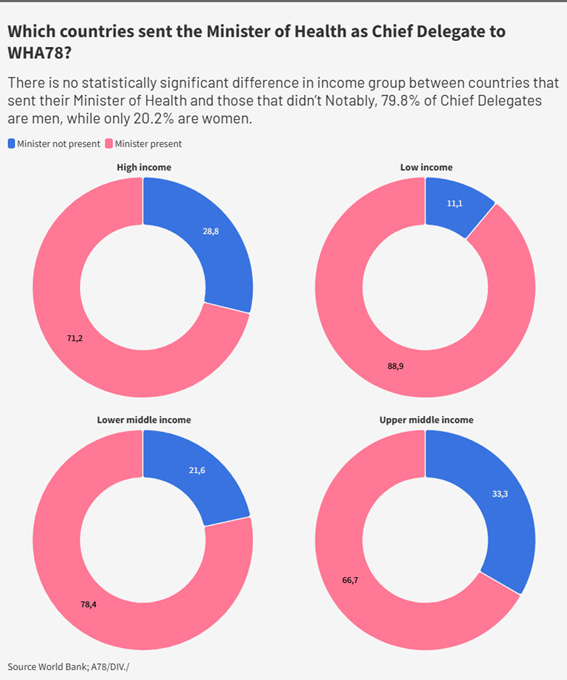

A final analysis of the delegation composition reveals significant aspects of power and equity. The Chief Delegate can be selected from a range of positions, but the Minister represents the highest-ranking public official a country will send. While there is no significant difference in income group between countries that appointed their Minister of Health as Chief Delegate and those that did not, low- and lower-middle-income countries are more likely to do so (Figure 2). This may reflect a strategic decision to signal high-level political commitment and ensure visibility, despite having smaller or less resourced delegations.

Notably, only 20.2% of Chief Delegates are women, highlighting a persistent gender imbalance in global health leadership. This figure aligns with the global average of women in Cabinet positions but falls 7 percentage points below the share of women holding health portfolios specifically.

WHO funding pledge – New funding landscape?

A more direct way to understand dynamics of power and influence at the WHO is to follow the money. Amid a challenging global health financing landscape, Member States approved an increase in assessed contributions on May 20th, with dues expected to cover 50% of WHO’s core budget by 2031.

At the Assembly, a high-level pledging event for the WHO Investment Round (IR), attracted at least US$210 million in voluntary funding from Member States and non-state actors. The most striking announcement came from China, which earlier that day pledged US$500 million. It remains unclear how much of this is counted as part of the assessed contributions or as a voluntary contribution. However, based on our calculations, China’s voluntary contributions amounted to just 17 cents for every dollar of its assessed contribution. This new pledge, will probably increase this ratio- ahead of many countries and foundations, likely increasing Chinese influence. Member states agreed to pay more to WHO under a previously negotiated decision – a small but significant step to sustainably finance the organization.

The Novo Nordisk Foundation also made a notable leap climbing up to the 6th place among top pledgers for the investment round. With US$57 million pledged, it now surpasses most individual EU Member States. This might gives the foundation growing visibility and potential influence over agenda- and priority-setting. Given that Novo Nordisk is the maker of the blockbuster drug Wegovy/Ozempic and that it has already engaged with WHO on to address non-communicable diseases, this raises urgent questions about accountability, transparency.

This will test the limits of WHO’s Framework for Engagement with Non-State Actors (FENSA), since the limits that FENSA poses to the use of financial contributions from private sector entities, do not apply to the Novo Nordisk Foundation, which might not be considered a private sector entity, but a philanthropy.

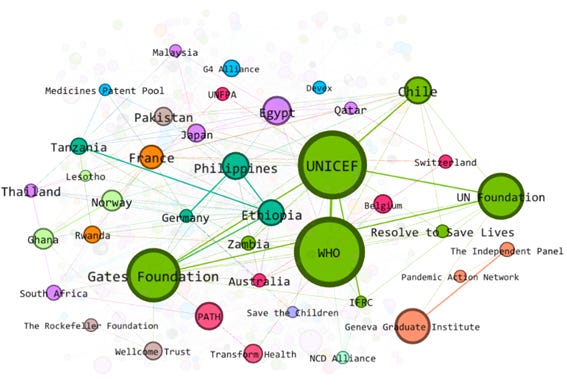

The Global Health System keeps searching for hierarchy.

When looking into who hosted more events, and the centrality of the actors - or who connects more actors and areas - we still see WHO and other IGOs together with Member States placed in the middle, co-hosting several events, but also connecting and bridging different areas (Figure 3). Large foundations (i.e., Gates Foundation and Wellcome Trust) who have played a key role in the Grand Decade of Global Health remain relevant together with Public-Private Partnerships and other Global Health Institutions (e.g., Global Fund, MMV, MPP, or Gavi).

On the outermost part of the figure, we find organizations that host events largely focused in one area, not connecting actors in a transversal way. For example, the NCD Alliance co-hosted at least seven events, five of them co-hosted with the pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim.

Network of events and hosts during the 2025 WHA. Orange dots represent events. The closer to the center an actor is, the more capacity the actor has to connect different parts of the system. The larger an actor, the more events it co-host.

To visit the interactive graph, click here.

It's not (only) about size, but the capacity to connect

An important way to assess this dense network of actors and relationships is to consider not only how many events each actor participates in, but also their role in bridging otherwise disconnected parts of the system (Figure 4).

For instance, Egypt and the Philippines stand out as key connectors between Global South governments and broader multilateral discussions. Despite not having the highest overall visibility, its position allowed it to link actors that might not otherwise have engaged directly. Meanwhile, France, as a major donor country, occupies a central role in tying together Northern and Southern governments, philanthropic actors, and international agencies—acting as a pivotal point in spaces where different agendas converge.

Not all strategic bridges in the network are Member States. A range of non-state actors also play a vital role in connecting disparate parts of the global health landscape. Academic institutions like the Geneva Graduate Institute, philanthropic foundations such as the Gates Foundation or the Rockefeller Foundation or even media platforms like Devex act as bridges by amplifying voices across sectors and linking spaces that often operate in silos. Some of these actors don't always dominate by volume or frequency, but their positions in the network reveal their power to convene, translate, and connect.

Delegation size and the ability to organize or participate in side-events during WHA are not exclusive indicators of power and influence in global health governance—and likely not the most important for achieving global equity and justice. However, they can serve as proxy indicators.

The absence of the United States signals a turning point, creating space for other actors to pursue new strategies, search new alliances and provide new funding sources in the system. It remains unclear how philanthropic foundations, public-private partnerships and global health institutions, which have been a key feature of the Global Health System in the last couple of decades, will shift in light of the current funding and governance challenges. The rising influence of some member states, the withdrawal of others, the regionalization of global health and the centrality of WHO and its Member States seem to offer some patterns to look at in the future.

Ultimately, it is the network of relationships and connections—not merely individual visibility or the ability to send large delegations—that determines who can truly shape the global health agenda. Actors with the capacity to wield its network power to build bridges across regions, sectors, and diverse agendas will become pivotal to the system’s functioning.

Amidst uncertainty and funding challenges, the key question for the years ahead will be whether this evolving model can uphold the shared goal of global health as a public good, or whether new power dynamics and fragmentation will erode the principles of equity and justice that should lie at the heart of the system.

Did a colleague forward this edition to you? Sign up to receive our newsletters & support Geneva Health Files!

Global health is everybody’s business. Help us probe the dynamics where science and politics interface with interests. Support investigative global health journalism.