Strengthening Primary Health Care to Achieve Universal Health Coverage: a Tunisian Perspective

Newsletter Edition #181 [A View From The Field]

Hi,

We have something different for you today.

Our readership has appreciated views from the field. We will now occasionally bring you essays and perspectives from capitals into global health Geneva. The goal is to keep our ear to the ground, so that discussions here begin to make more sense and have a wider context than the echo chamber that Geneva sometimes is.

We bring you a refreshing essay from one of our fellows who has joined us this year. Skander Essafi, is a medical doctor from Tunisia, who shares his views on the importance of primary health care as a route to achieve universal health coverage.

We also have a brief update on WHO’s leadership announcements made this week.

Watch out for our analysis later this week, on the third meeting of the Working Group on the amendments to the IHR currently taking place in Geneva.

Finally, check out our upcoming workshop on Global Health Negotiations at WHO [April 28, 2023], this will collectively look at INB and IHR discussions so far. Sign up here?

Like our work? Consider supporting our journalism that ensures nuance, detail, and accuracy. Readers paying for our work helps us meet our costs. Thank you for reading.

Until later!

Best,

Priti

Feel free to write to us: patnaik.reporting@gmail.com or genevahealthfiles@protonmail.com; Follow us on Twitter: @filesgeneva

I. A View From The Field

Strengthening Primary Health Care to achieve Universal Health Coverage: a Tunisian perspective

By Skander Essafi

The World Health Assembly, convening next month, will vote on a resolution on “Universal Health Coverage (UHC): Reorienting health systems to primary health care”. Tunisia, as many other countries in similar contexts, struggle to implement their health care reforms for UHC.

In the name of health in all policies, there should be bolder governance, stronger financial management and transparency to involve all professions from the public and private sector.

In this essay, I share my experience as a doctor in Tunisia and how I came to realize the importance of universal health coverage in improving overall health outcomes.

Despite previous efforts and political will, Tunisia must make sure that primary health care services are holistic for a better continuum of care in the population, running no financial hardship. This can also be done by collaborating and sharing best practices within countries of the same context, so that solutions are sustainable and better adapted to the specificities of the respective countries.

THE DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

When I chose to study medicine in 2010, I did not expect to get involved in the pedagogy of medical curriculum, in the Tunisian healthcare sector reform, and in global public health.

In my first-year introductory lecture to community medicine, I was inspired by one of my professors who made a persuasive argument about major health issues in Tunisia and how general practitioners can address them in primary health care. He also touched on those issues from the perspective of the determinants of health, which was the first time I got to know about it.

It was through the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations that I got more knowledge and practice about the determinants of health. I got actively involved in projects outside of medical school, and experienced the true linkage between health and poverty, income, environment, access to healthcare, to name a few. I also had the opportunity to take part in discussions at the national level via the societal health dialogue in 2014 to reform the healthcare sector after the Tunisian revolution, but also at the international level in the World Health Assembly 2017 and the United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties in 2015 and 2016.

Unfortunately, while working at the Tunisian hospital, I noticed that it did not prioritise these determinants. Little attention was brought to the transportation of patients, their catastrophic health expenses, the impact of their environment and working conditions on their (physical and mental) health.

For these reasons, I wanted to focus my career on building a stronger relationship with my community through a family medicine specialty and in primary healthcare, trying to address their needs from a research and policy perspective. I am currently pursuing a master degree in health economics and management.

FAMILY MEDICINE AND PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

My experience in family medicine was very different from my peers. Since my early years in medical school, I was keen on providing holistic care, addressing the determinants of health, and build on what has been acquired in primary healthcare in Tunisia. I did in fact learn from doctors who were passionate about their job, doing their best to address their patients' needs despite the lack of resources, and eager to transmit this passion to the new generation of family doctors.

It was also thrilling to discover that I was be part of the second national cohort of family medicine trainees. This came after the reform of the medical curriculum that was voted after the Tunisian Revolution in 2012 to consider family medicine as a stand-alone medical specialty with dedicated mandatory training program of 3 years, in order to meet the worldwide standard requirements of general practitioners at the post-graduate level.

It was a privilege to take part in a new and dynamic project, being able to provide feedback easily. However, this initiative was risky because of the political and social implications of reforming primary health care. There was a lot of resistance from current general practitioners in regards to the transfer of their degree.

Additionally, other medical specialists and lobbyists perceived family medicine as a threat to their discipline and personal interests. I personally faced several arguments with general practitioners and other specialists who were pushing to see this reform fail. These observations showed a lack of strategy towards the future of this new generation of family doctors, their role and contribution to primary healthcare and medical academia, as well as their remuneration.

All these reasons could only ‘force’ my colleagues to follow this track as the shortest one in post-graduate studies and to look for a better future abroad afterwards. I was holding my hope and still think that there is a more potential to reform the system in the longer term.

I was initially very enthusiastic about engaging in primary healthcare, and advancing my training through research projects, further education and involvement in the decision-making of my curriculum. An initiative I launched in a primary healthcare center was to study and measure the impact of therapeutic education for diabetic patients individually and in groups. I addressed this project by learning about the discipline of therapeutic education in diabetes, by collaborating with the staff of the center and by connecting with the patients in order to respond to their specific needs.

THE COVID-19 EXPERIENCE AS A HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL

Another learning experience was the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, when I was already training at the Department of Infectious Diseases. I was a part of the team that managed the first COVID-19 patients in the country.

There was an opportunity to unite efforts with other stakeholders such as the regional health authority, the COVID-19 testing centers, other hospitals and departments as well as GPs to standardize the regional response to the pandemic. This coordination showed the need to develop a centralized electronic health record system, which could save time, paperwork and support a more efficient response and surveillance. I also had experiences at the COVID ambulatory and onsite Emergency Department as well as rural hospitals. I took part of a mission to advise patients to stay at home or go to the hospital, and to ensure that they have the appropriate information related to COVID-19.

However, the most intense experience was during the peak of the waves, where very sick patients couldn’t find beds at the hospital, and with the intervention team we had to wait for the approval of the Intensive Care Unit before transporting them with the adequate medical care. It was usually a sensitive situation, especially when collaborating with the families of the patients. This is where coordination is key to centralize the information in hands within the intervention team, with the receiving institutions as well as the family.

WORKING IN GERIATRICS

Another significant experience was in the private sector at a geriatrics practice. This experience was mind-blowing for me: first, because the geriatrics discipline is only addressed at the medical university, and there aren’t well established geriatrics consultations and departments at the hospital. I was blessed to have the opportunity to work with and shadow a geriatrics specialist. I was amazed by the exposure to elderly care and approach in general. This experience highlighted the love for a discipline which would have been almost inaccessible at my medical residency training otherwise. Secondly, it showed that public-private partnerships are possible as long as they serve a specific purpose, which can be academic but also to fill in a gap in a certain area, and under certain agreed terms.

All these experiences reflect what Tunisia has acquired in the past decades to improve health coverage, and putting efforts in primary health care. Following the Alma Ata Declaration supported by the World Health Organization and signed in 1978, a major focus has been made to increase the accessibility to primary health care centers, especially in rural areas of the country. There was considerable progress in the vaccination coverage, in reproductive health as well as programs tackling chronic diseases (namely hypertension and diabetes). Tunisia has been showing exemplary efforts in the region to address UHC by focusing on Primary Health Care.

Since the rise of the Arab spring in 2011 within the Middle East and North African (MENA) region, the resulting the unstable political sphere, and the overall governance of the system, the healthcare system has become very fragile. It has not been able to progress at the previous pace, in addition to being affected by private sector domination, public sector corruption and the instability of health services. We can see that the lack of a new economic order to address inequities, which determine access to nutrition, essential medicines and affordable care, reflect on the health of a population. It is obvious that the commitments of the Astana Declaration call cannot be easily fulfilled in the MENA region.

Skander Essafi is a medical doctor from Tunisia pursuing a master in health economics and management, passionate about improving population health and primary healthcare. Write to Skander at skander.es@gmail.com.

II. PODCAST CORNER

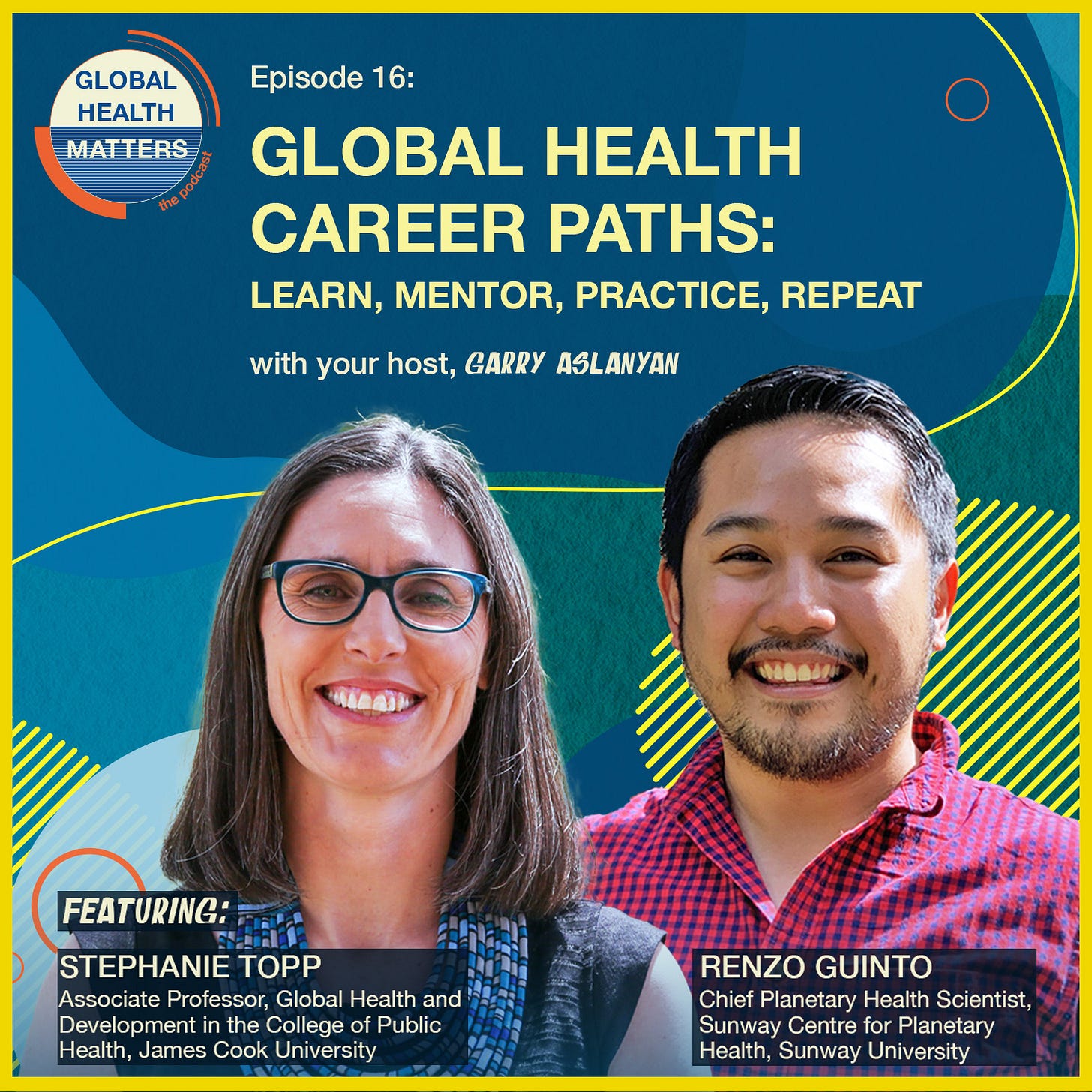

Global health career paths: learn, mentor, practice, repeat

Two career professionals in global health share their knowledge of how they chose their path and giving clear guidance on ways to get the support needed to increase opportunities to make a difference in addressing global health challenges.

Host Garry Aslanyan speaks with the following guests:

Stephanie Topp is an Associate Professor in Global Health and Development at James Cook University in Australia. Originally trained as a historian, Steph applies her social science background to health systems and policy research. Steph's rich experience in global health implementation gained in Zambia in 2008-2010 and 2012-2015 has been valuable to inform her thinking around how health equity can be enhanced for marginalised populations in Australia.

Renzo Guinto is a Filipino researcher who is passionate about addressing the determinants of health. As Chief Planetary Health Scientist of Sunway Centre for Planetary Health in Malaysia, Renzo engages in research and advocacy at the interface of climate change and health.

Listen here

Garry Aslanyan is the host and moderator of the Global Health Matters podcast. You can contact him at: aslanyang@who.int

This podcast promotion is sponsored by the Global Health Matters podcast.

If you wish to promote relevant information for readers of Geneva Health Files, for a modest fee, get in touch with us at patnaik.reporting@gmail.com.

III. POLICY UPDATES

Key leadership appointments made to drive WHO strategic direction and initiatives: WHO

Also see: WHO’s New Leadership Team Is a Mixed Bag of Political Appointees and Specialists: Health Policy Watch

Excerpts from WHO’s statement:

“The World Health Organization (WHO) has appointed five new senior figures to its headquarters leadership team in Geneva.

The new appointments follow the reappointment of Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to his second five-year term as Director-General. The overall leadership team has been consolidated to align with the Organization’s priorities for the next five years and will work closely with the Director-General to drive forward these priorities and WHO’s ambitious transformation agenda.

New members of the headquarters leadership team:

Jeremy Farrar will become WHO’s Chief Scientist as of 8 May 2023. The appointment of Dr Farrar was previously announced in December 2022. In this role Dr Farrar will oversee the Science Division, bringing together the best experts and networks in science and innovation from around the world to guide, develop and deliver high quality health policies and services to the people who need them most. Prior to joining WHO Dr Farrar was Director of the Wellcome Trust.

Ailan Li will become Assistant Director-General for Universal Health Coverage, Healthier Populations as of 8 May 2023. In this role Dr Li will oversee the Organization’s efforts to promote better health and well-being through interventions relating to the environmental, social, and economic determinants of health, including climate change, tobacco control, chemical safety, road safety, food systems and nutrition, physical activity, air pollution and radiation, through a One Health approach.

Yukiko Nakatani will become Assistant Director-General for Access to Medicines and Health Products as of 2 May 2023. In this role Dr Nakatani will oversee the development and implementation of WHO’s norms and policies to ensure equitable access to quality medicines, vaccines and diagnostics for all populations everywhere, including for preventing and responding to epidemics.

Razia Pendse will become the Chef de Cabinet as of 4 May 2023. In this role Dr Pendse will head the Director-General’s Office, helping to drive the Organization’s priorities and initiatives and will ensure alignment within the WHO leadership team and across the three levels of WHO.

Jérôme Salomon will become Assistant Director-General for Universal Health Coverage, Communicable and Non-communicable Diseases as of 17 April 2023. In this role Dr Salomon will oversee a broad portfolio of technical programmes covering HIV, viral hepatitis, sexually-transmitted infections, tuberculosis, malaria, neglected tropical diseases, mental health, substance use disorders, and noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and cancer.

The portfolios of existing members of the headquarters leadership team:

Samira Asma will continue as the Assistant Director-General for Data, Analytics and Delivery for Impact.

Bruce Aylward has been appointed Assistant Director-General of the Universal Health Coverage, Life Course Division as of 4 May 2023.

Hanan Balkhy will continue as Assistant Director-General for Antimicrobial Resistance.

Catharina Boehme will become Assistant Director-General, External Relations and Governance as of 4 May 2023. In this role Dr Boehme will lead WHO’s strategic engagement in the areas of governance, resource mobilization and partner relations. Her portfolio will include critical Member States processes, such as their negotiation of a pandemic accord, the reform of WHO’s governance and the implementation of recommendations on sustainable financing.

Chikwe Ihekweazu will continue as Assistant Director-General for the Division of Health Emergency Intelligence and Surveillance Systems in the Emergencies Programme.

Michael Ryan will continue as Executive Director of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme.

Raul Thomas will continue as Assistant Director-General for Business Operations.

Improving access to novel COVID-19 treatments. A briefing to Member States on how to navigate interfaces between public health and intellectual property: WHO

Pandemic Accord: MSF’s comments on equity provisions in zero draft: Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign

IV. WHAT WE ARE READING

News:

The WHO Turns 75: Health Policy Watch

Pharmaceutical CEOs to G7: Protect Intellectual Property Rights and Pathogen Access in WHO Pandemic Accord: Health Policy Watch

US Abortion Pill Ruling Could Have Chilling Effect on Other Drug Approvals: Health Policy Watch

Eli Lilly warns EU will miss out on key drugs under planned change to patent rules: Financial Times

Right to Health: The fight over who'll pay hospital bills of India's poor: BBC

Why Neutrality Is Obsolete in the 21st Century: Foreign Policy

Devex CheckUp: A global health wish list for the Spring Meetings: Devex

Don’t Normalize the Taliban’s Despotic Regime: The Diplomat

Research:

Flexibly funding WHO? An analysis of its donors’ voluntary contributions: BMJ Global Health

What's the ideal World Health Organization (WHO)? Health Economics Policy and Law

IFIs need a well-defined role in global health: Chatam House

Striking fair deals for equitable access to medicines: DNDi in The Journal of IP Law & Practice (See also Pro-access policies)

Global health is everybody’s business. Help us probe the dynamics where science and politics interface with interests. Support investigative global health journalism.