“Some aspects of innovative finance are dressed up to be what they are not": Peter Sands, The Global Fund

Newsletter Edition #193 [The Files Interview]

Hi,

Global health must open up and pay attention to external perspectives and transcend “internal debates”. Looking farther afield for solutions to problems that affect health has become a necessity. It is refreshing when leaders in global health speak their mind and bring a dose of pragmatism to policy-making, particularly in Geneva.

I am very pleased to bring you today, insights from Peter Sands, who has led The Global Fund for more than half a decade now. When Sands was chosen in 2017 to led the Fund, there were the usual detractors, but many would admit that global health has got richer on account of Sands’ leadership. (Here’s a story I wrote when Sands was appointed.)

In my former life as a financial journalist reporting on banking and monetary policy, I first met Peter Sands in 2007 in Mumbai, when he was the CEO of Standard Chartered. I recall his grace and openness to address questions even back then.

In this interview, he shares his perspective on the changing landscape of global health governance and financing. We hope this is useful at a time when financing for PPR dominates multiple forums in international development.

In case you missed it, check out another lucid interview on global health financing that we published last week - with Attiya Waris who is the UN Independent Expert on foreign debt, other international financial obligations and human rights.

Like our work? Consider supporting our journalism that ensures nuance, detail, and accuracy. Readers paying for our work helps us meet our costs. Thank you for reading.

Until later!

Best,

Priti

Feel free to write to us: patnaik.reporting@gmail.com or genevahealthfiles@protonmail.com; Follow us on Twitter: @filesgeneva

I. THE GENEVA HEALTH FILES INTERVIEW

“Some aspects of innovative finance are dressed up to be what they are not."

Peter Sands has been steering The Global Fund since 2017, continues to bring much-needed clarity to global health policy-making and to address the intractable challenges of deep-rooted diseases. The Global Fund invests US$4 billion a year to fight HIV, TB and malaria, and raised US$ 15+ billion in 2022 in its last round of replenishment.

In this comprehensive interview, Sands, a former banking chief, cuts through the chase and tells it like it is. From financing for pandemic preparedness and response, to the urgent global health implications of climate change, to his more nuanced views on innovative finance, Sands spoke with Geneva Health Files recently. He chooses his words carefully and shares his considered views on both technical and political issues in global health.

[GHF] Q1. What is the role of the Global Fund post COVID-19 and for pandemic preparedness in general, going forward?

[Peter Sands] We have always played a role in pandemic preparedness, even when we weren't explicitly doing so. And indeed, there was an interesting article in The Lancet in February 2001, which looked at the fact that about a third of global fund investments contributed to pandemic preparedness, because we are the largest multilateral provider of grants for health systems. And because our core mission is around fighting infectious diseases, we are investing in all the components of health systems that are vital to prevent, detect, and respond to any kind of infectious disease threat. We saw that play out in practice in the COVID-19 pandemic, because for many countries, if you actually look at the way they responded, much of the infrastructure that we are using, the people, the systems, the technology, the molecular diagnostics, laboratories, and the supply chain was all stuff that we had invested in and built for fighting HIV, TB, and malaria.

The difference that is embedded in the strategy is now to ensure a bit more intentionality. So that when we are invested in the laboratory network on disease surveillance systems, to do it very deliberately, with a multi-pathogen perspective. We are looking beyond the immediate diseases, and helping countries build capabilities that will provide better ability to prevent, detect, respond to future threats, whatever they are.

You are seeing this in a whole range of different types of investments we are doing, like whether it is in wastewater surveillance or enhancement of mobile X-ray or molecular diagnostics, or the way we are building out supply chains, or even the way that the sort of community health worker networks are being developed. Obviously, in the pandemic itself, we have played a significant role through our COVID-19 response mechanisms. So in terms of grants, we were the largest provider of grants for lower and middle income countries for everything other than vaccines. So COVAX did vaccines, but we did a huge amount on diagnostics, on PPE, on oxygen, on enhancements to health systems. Some countries that needed rapid enhancements to their supply chain or to their Intensive Care Units. A whole range of different things that needed to be done. Community systems has been a significant has been a significant aspect.

We are continuing to use both our core grant portfolio and COVID-19 Resource Mobilisation for investments in these components of health systems. One thing I would emphasize is the point of integration into pandemic purpose. A very high proportion of the things you want to invest in for pandemic preparedness are the things you want to invest in anyway for fighting existing infectious diseases. You might argue that some aspects of zoonotic spillover type stuff are specific to pandemics. The core health system stuff is basically the same stuff.

[GHF] Q2. In current global health negotiations (Pandemic Accord & amendments to the IHR], there isn't enough emphasis on health systems strengthening. A lot of it is about response and not so much prevention, many believe. What are your thoughts on this? How should countries craft obligations on health systems strengthening in these new rules?

[Sands] I think there are two answers to that question.

One is the bias towards response has always been there. Between Standard Chartered and the Global Fund, I spent some time at Harvard doing work on things like the interaction between finance and economics, and pandemics. And it is a bit sad looking at some of the things I wrote then because nobody was paying attention. But at the time, that was one of my arguments against things like the Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility, is that I felt it was putting too much political capital and emphasis on response, rather than on preparedness.

I mean, I think, I'm not sure whether a sort of rules-based approach to health systems is ever going to be massively effective, because the way health systems work, and because the needs of the communities are very context specific. But on the other hand, I think the concern is absolutely right, which is that we should be investing more in the health systems components.

What we saw with COVID also, this has been a limiting factor. People get very excited by and rightly, about access to medicines and so on. But then you very quickly run into the bottleneck, that is the health systems themselves and their ability to deliver. And so I think it is right to be concerned.

I always make the point that people always get more excited about fire engines than they do about things like fire building codes, and fire retardant materials. But if you want to understand what has made the biggest difference in reducing deaths due to fires, it has not been improvements in fire engines. It has been improving in fire retardant materials, building codes, and all the kinds of nitty-gritty, preparedness and prevention stuff. And that's what we have got to do.

But I would also keep insisting on this fact that we can't see it as a bright line between... this is for existing diseases and this is somehow for pandemics. I look at the inequities around this area, and obviously, there is a set of inequities that everybody focuses on, which is the inequities around access to medical countermeasures, right? They didn't get vaccines, they didn't get diagnostics and so on.

There is a slightly more subtle one, which is who gets to decide what gets treated as a pandemic? I can tell you if you had a disease that arrived tomorrow, that it was in every country in the world; that 10 million people a year fell sick of; that it killed over 1.5 million people; that had a fatality rate higher than COVID-19.... So imagine a new disease like that, it would be called a pandemic. It is TB. So my worry is that if we allow for a particular set of things that are in the sense - privileged for pandemics - and pandemics are only defined, and of course, this would never be explicit, as 'things that might threaten to kill people in rich countries', then we actually inadvertently widen the inequities within global health.

[GHF] Q3. Sure, point taken. That is where it is so contested and political. Who gets to decide what is a pandemic.

So when you talk about the expanded role of the Global Fund mean, in terms of the size of the envelope going forward for PPR, what does that look like if you get into this in a big way? And how do you think we can prevent fragmentation of global health financing, not just the World Bank fund, but also potentially new mechanisms for financing (like the Green Climate Fund, affiliated to WHO member states) that some countries are now suggesting in the context of the negotiations?

[Sands] In a sense, we are in this in a significant way. And we invested more in total...more in health systems last year than we have ever done, and we will do more this year. Now, where that goes in the future will depend on, you know, the appetite of donors, and how this whole debate unfolds around financing mechanisms.

I suppose the point I would be making is, ultimately we have got to work out a way that works for countries, and is efficient and effective. As you say, there is significant fragmentation, and the trouble is that the institutional, political motivations here tend always to create new institutions. But this creates real difficulties at a country level. I would argue that the global health space is too fragmented already, and that we impose too great a burden on countries in terms of different reporting mechanisms, different assurance mechanisms, different governance requirements, and different time-frames in which to organize things.

So far, despite a lot of a rhetoric around wanting to sort of simplify and make it more responsive to country needs, actually, what we have done is made it more complicated. I think this is something that we need to think very hard about. We are actually making the deployment of the money less efficient.

And we got to appreciate that many of the countries that are most in need, require leadership bandwidth to deal with a lot of this stuff. And even if they can do it, you are diverting them from doing better things they should be doing. Much of this stuff is actually quite challenging to implement, particularly in resource-constrained environments. If you want to do gene sequencing of pathogens based on wastewater surveillance, in an environment where wastewater processes are, let's say uneven, then you have to think quite suffer. There is quite a lot of work to do to put that kind of thing in place. Distracting people for writing, sort of multiple submissions or reports to different funders, all supporting the same thing is not optimal.

[GHF] Q4 This emphasis on raising resources domestically [for PPR], there are limits to that as well, with shrinking fiscal space and so on. It is often argued that adequate finances cannot be raised internationally and that countries should fix this themselves. But that is not so easy, right?

[Sands] No, it isn't. And also, it is very hard to generalize. When you are talking about low- and middle-income countries, you are talking about some countries which have very significant financial resources, and ability to do things themselves. But you are also talking about countries which are extremely fragile, have no fiscal capacity, and frankly, have higher priorities. Such as for example, they have very high maternal death rates. So you have very high infant mortality. And pandemic preparedness is something with very high externalities, right? That everyone in the world benefits from each country getting better at it. And therefore, it is something that it makes sense for other countries to support. And we can't expect the poorest countries to pay for it themselves, because it simply wouldn't make sense for them to do so. And they don't have the resources.

One of the aspects in the discussion around pandemic preparedness and response is, it becomes very state-driven and technocratic - very much about the medical response and very much about what the governments are doing. Those are important elements. But one thing we have found in two decades of very successful fighting against infectious diseases, is that if you don't have the communities as part of the fight, then you won't win. You are much more powerful...[with communities]. And indeed, if you look at the success or failure of many countries' COVID-19 responses, a lot of it was around could governments actually get societies to trust them , or could they sway people to do what they wanted them to do.

The whole community and people aspect of pandemic preparedness, I fear gets a bit lost. There is a fair amount of analysis that says that one of the biggest assets you have when you run into one of these situations, is trust. But you build trust, by engaging people, but you also build trust by delivering on their needs now. So we have to build an approach to pandemic preparedness and response that engages communities. And that also doesn't draw a distinction between their existing needs in fighting infectious diseases, and their potential future needs. You can't just turn up when something [comes up] that might threaten other parts of the world, and expect people to take you seriously.

[GHF] Q5. Coming to your recent comments on the limitations in innovative financing, their effectiveness in dealing with resource-constraints in global health - you seem to be skeptical about such approaches. From climate finance to now global health, innovative financing is being sold as a policy approach, even in the context of raising sustainable finance for WHO. Can you elaborate on your views?

Also, debt swaps are being suggested as one way to liberate greater resources for global health. Do you think they will be effective in the context of PPR financing?

[Sands] It is not that I am against innovative finance. In fact, there are some aspects of innovative finance that I find...actually, we are enthusiastic about debt swaps. So I want to be clear, we do debt swaps. I think we have done $260 million of debt swaps already. And we are actively pursuing other debt swap arrangements. We also do blended finance deals in which we essentially subsidize the interest costs on MDB loans to incentivize countries to use them for health purposes.

But let us be clear both of those are essentially taking different forms of overseas development assistance and using them... but they not generating new money. Doing a debt swap of concessional debt, and having that forgiven, and turning it into [investments in] health is a good thing to do, but it is not new money.

The issue I have, with some aspects of innovative finance, is they are dressed up to be what they are not. When people aren't looking at the underlying economics, and they aren't being sufficiently rigorous, and they are pretending that the private sector is involved, when actually the private sector is making money out of them. We have to be very clear about what's actually happening in these transactions, or we run the risk of kidding ourselves.

Because there is a political imperative, often, to find new sources of money and get the private sector involved, there is a bit of a desire to rush over over those bits. The Pandemic Emergency Facility was a fraud concept from the beginning, and it didn't work.

And things like the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), which is perfectly sensible as a way of encouraging governments to make commitments. Governments find it easier to spread their commitment over a longer period. But we should not kid ourselves - the private sector does not put money into it, the private sector makes money out of it. And it is not expanding the ODA.

[GHF] Q6. What are your thoughts of Payments by Results? There is a lot of interest from impact investors, and global health in general has embraced using Payments by Results - but we also know the development outcomes cannot always be accurately measured by indicators and this may not be the best approach.

[Sands] On the payment for results side, there are some opportunities. We at the Global Fund do more with private sector partners than anybody else in the global health space. We have a lot of complicated structures with which we work.

But the reason I come across sounding skeptical, is that we should be very clear, if we want to meet the needs of the very poorest all on issues that are around sort of basic systems and saving lives, we shouldn't kind of kid ourselves that innovative finance is the way to do that. It's not going to be the solution to doing that. I have a little bit of a worry that if we put too much attention into that, it is a kind of excuse for not saying, actually what we need is for the donor governments in the world to be prepared to put their hands in their pockets to make grants. Because if we make it too complicated, and all we are doing is increasing the transaction costs.

So there is a role for innovative finance, but there is bad innovative finance and good innovative finance. And we need to be very thoughtful about where we use it. And it shouldn't be an excuse for actually not delivering on overseas development assistance.

[GHF] Q7. How do you think the governance of The Global Fund will evolve in the future, in light of the decolonizing movement? Donors at The Global Fund have more latitude to influence the governance, than they are at for example, WHO.

[Sands] I think the Global Fund already has one of the most inclusive governance systems in the global health and development landscape. We have 20 voting seats on our board, three of them are for civil society. And the balance between donors and implementers. And they also include the private sector. It isn't just about rich countries and poor countries, it's also about non-state actors. And much of the debate is about country versus country. I think it is important, but it's not the whole story. The inclusion of non-state actors is really important. So five of our both voting seats are non-state actors in total.

And the other thing about the Global Fund model, which is different from many other organizations, is that we don't actually set the priorities. What the countries actually do with the money that we award them is, is set by them, because we have these Country Coordinating Mechanisms. And again, they are not only the government. There are rules, the policies around the Country Coordinating Mechanisms, is they have to be inclusive of different components of society, including NGOs, communities, private sector, and so on. And so the whole idea is consistent with some of the themes around decolonizing global health that we should be an enabler of what countries and communities are seeking to do. The governance mechanisms, both global level and at the country level, are sort of designed to facilitate that.

Now, of course, you can always be enhancing and we are continually sort of tweaking and enhancing them. But the model is definitely not, you know, a donor driven board with donors telling countries what they are going to do with them. That just isn't the way the Global Fund works, or has ever worked.

[GHF] Q8 What's ailing global health? What keeps you up at night?

[Sands] One thing I think we are in danger of is focusing too much on the last issue. You know, the whole fighting the last war problem, which is not to say we shouldn't be concerned about pandemic preparedness, but the reality is climate change is changing the rules of the game in global health right now. And it is killing people right now. We are collectively behind the game in our response to that. We are not properly linked in with the whole climate change community. The global health consequences of climate change are only barely on the agenda of the climate change [discussions]. That is a real problem. Because if you look at what happened in Pakistan last year, if you looked at what has happened to Mozambique and Malawi….I have just been to Chad. I mean, this is with us, this is real.

The interplay of that, and conflict is creating a dynamic where we need to be, we need to be thinking differently about notions of resilience. So the notion of resilience in a climate change context, is different from resilience in the kind of the next COVID-19 context. And likewise, you know, one of the things that we have seen is that, in conflict situations, the civil society networks are one of your strongest ways of dealing with and ensuring continuity of service in conflict.

I also worry that we get too wrapped up in our internal debates, and not focused enough on this what's actually happening in the world? And that the answer the global health community to every problem is to create something new, and which just makes an already overly fragmented ecosystem, even more in fragmented.

If you think back to your background in financial services, in the global financial world, the number of institutions that really make a difference - the IMF, the World Bank, the FSB (Financial Stability Board), the BIS (Bureau of International Settlements), that's it really. And they all have huge significant resources and authority and all that kind of stuff. And then the Global Health landscape, just the profusion of entities. But I'd say I think the biggest thing for me is this, I worry that we are in a world where the combination of climate change and conflict is going to be driving the dynamics of global health. And we need to have our act together to respond to that, because otherwise, the health consequences will end up fueling the political conflict issues as well.

[GHF] Q9 Do you miss banking?

[Sands] No…. I love what I do. I enjoyed what I did then. But I like what I am doing now.

Get in touch with The Global Fund: press@theglobalfund.org

Alyssa Chetrick contributed to the production of this interview.

II. PODCAST CORNER

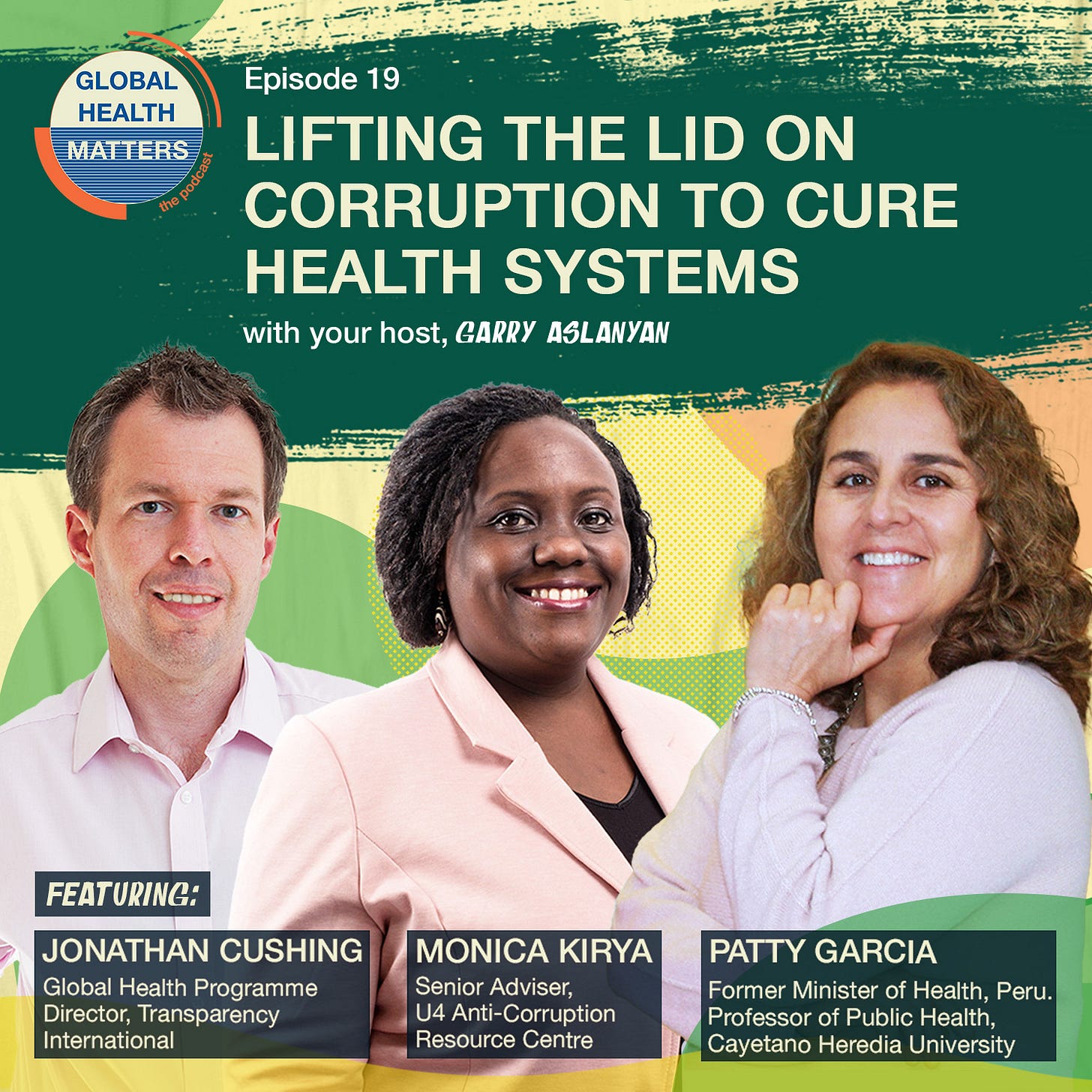

Lifting the lid on corruption to cure health systems

The subject of corruption in global health is often muted and totally taboo for some to even think it. This podcast episode on corruption is opening up the discussion to a wider audience to understand the scale of the problem for health systems and to hold more people to account for their part in the resulting damage.

For this Global Health Matters podcast episode, host Dr Garry Aslanyan delves deep into the topic to uncover the sources, the offenders and the solutions from our panel of experts. He speaks with the following guests:

Monica Kirya: Senior Program Advisor at the U4 Ant-Corruption Resource Centre

Patty Garcia: Professor at the School of Public Health at Cayetano Heredia University (UPCH) in Lima, Peru. She is also the former Minister of Health of Peru.

Listen to the episode.

Garry Aslanyan is the host and moderator of the Global Health Matters podcast. You can contact him at: aslanyang@who.int

This podcast promotion is sponsored by the Global Health Matters podcast.

If you wish to promote relevant information for readers of Geneva Health Files, for a modest fee, get in touch with us at patnaik.reporting@gmail.com.

III. WHAT WE ARE READING

News

Review finds WHO support for DRC sex abuse survivors 'not sufficient': Devex

Moderna signs deal in Shanghai with view to developing mRNA medicines : Reuters

WHO and Africa CDC work to mend their fractured relationship Devex

Sentenced to Tuberculosis: How Prisoners Are Denied the Right to Health : Health Policy Watch

Emergency aid leaders and donors met in Geneva. Here’s what happened : The New Humanitarian

WHO Launches New Guideline for Protecting Children from Unhealthy Food Marketing : Health Policy Watch

AI? Brain manipulation? WHO’s new chief scientist aims to anticipate global challenges : Science.org

Opinion: Why we launched a health investment platform for primary care : Devex

The Global Fund embraces integration of chronic diseases : Devex

The good, the bad, and the ugly of Macron's Global South summit : EU Observer

Exclusive: Indian firm used toxic industrial-grade ingredient in syrup : Reuters

The Global Fund embraces integration of chronic diseases : Devex

Journals & Reports

Sick Development: How rich-country government and World Bank funding to for-profit private hospitals causes harm, and why it should be stopped - Oxfam

The Origins of Covid-19 — Why It Matters (and Why It Doesn’t): NEJM

IV. WHAT WE ARE TRACKING

Intergovernmental Negotiating Body [INB6]: July 17-21

Working Group on Amendments to the International Health Regulations: July 24-28

Global health is everybody’s business. Help us probe the dynamics where science and politics interface with interests. Support investigative global health journalism.