Human Rights Challenges in the Pandemic Treaty Negotiations [Guest Essay]

Newsletter Edition #27 [Treaty Talks]

Hi,

The discussions towards a new Pandemic Accord at WHO, is currently a veritable soup of a broad range of political priorities for WHO member states. While the negotiations are very much fluid at this stage, matters such as human rights, among a wide range of other areas, could be relatively easily traded for other matters of “greater priority” by countries. In fact, experts say, in these kinds of negotiations, human rights considerations are often the earliest casualties.

There are early indications that this could be so - some countries believe that a WHO treaty is not a place to negotiate human rights. This is even as COVID-19 resulted in many WHO member states committing flagrant violations of human rights.

In today’s edition we bring you a guest essay from a group of human rights scholars, keen on shaping the discussions towards a new Pandemic Accord in a way that reflects such considerations in the governance of pandemics. In this piece, they pick apart current provisions and suggest priorities for the on-going negotiations.

The authors say, “Framing the substance of the Pandemic Treaty, human rights must be central to global health obligations, as the right to health provides a central normative foundation in preparing for and responding to pandemics.”

We hope you enjoy reading this timely and important commentary on a somewhat neglected area in the on-going negotiations of global health law reforms.

As countries get deeper into defining principles and provisions in a new pandemic accord, we will continue to bring you expert voices to illuminate some of these issues on the table.

(Also sharing a recent event I participated in on the sidelines of the Human Rights Council earlier this year, organized by Sexual Rights Initiative: Health, Human Rights and Capitalism.)

Like our work? Consider supporting our journalism that ensures nuance, detail, and accuracy. Readers paying for our work helps us meet our costs. Thank you for reading.

Until later!

Best,

Priti

Feel free to write to us: patnaik.reporting@gmail.com or genevahealthfiles@protonmail.com; Follow us on Twitter: @filesgeneva

I. GUEST ESSAY

Human Rights Challenges in the Pandemic Treaty Negotiations

By Benjamin Mason Meier, Roojin Habibi, Judith Bueno de Mesquita, Sara L.M. Davis, Timothy Fish Hodgson, Sharifah Sekalala, Margot Nauleau, Saman Zia-Zarifi

In strengthening human rights in the development of the World Health Organization (WHO) convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic preparedness and response (CA+ or Pandemic Treaty), the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) of WHO Member States has considered the integration of human rights at various points in the Pandemic Treaty negotiations. However, the current INB Bureau text, compiling inputs from Member States, fails to mainstream human rights, stepping back from previous INB advancements and neglecting longstanding efforts to recognize the inextricable linkages between human rights and public health. The upcoming negotiations of the Pandemic Treaty provide a crucial opportunity to safeguard human rights in global health governance, addressing human rights limitations in the COVID-19 response and establishing human rights obligations to meet future pandemic threats.

This analysis explores necessary reforms to mainstream human rights throughout the Pandemic Treaty, whether by explicitly incorporating international legal obligations or by implicitly reflecting human rights norms and principles. Responding to human rights challenges in Pandemic Treaty negotiations, this analysis seeks to: examine the origins of the Pandemic Treaty; frame the legal imperative for human rights; chronicle civil society advocacy in INB negotiations; and analyze critical reforms to strengthen human rights.

This essay highlights key revisions necessary to strengthen the Pandemic Treaty to further the (1) right to health, (2) human rights-based approach to health, (3) permissibility of human rights restrictions in public health responses, and (4) imperative for international assistance and global solidarity – providing a human rights foundation for civil society advocacy and Member State negotiations.

Developing a WHO Treaty to Address Pandemic Threats

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the International Health Regulations (IHR) provided the principal global health law authority; however, states long faced challenges in meeting IHR “core capacities” to prepare for public health emergencies. The COVID-19 response revealed the limitations of international legal obligations, the political obstacles in following public health guidance, and the absence of meaningful accountability – weakening global solidarity under WHO governance. In September 2020, the WHO Director General appointed an Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR) to review the international health response to COVID-19, with the final IPPPR report recommending the adoption of a “Pandemic Framework Convention.” These recommendations for global health law reforms gave rise to proposals to develop a novel Pandemic Treaty alongside amendments of the IHR, establishing new legal authorities to prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from future pandemics.

Although WHO had rarely used its treaty-making authorities under the WHO Constitution, WHO Member States came to view a binding international convention as necessary to strengthen WHO authorities, support preparedness efforts, and generate new resources. The World Health Assembly resolved in November 2021 to “draft and negotiate a convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic preparedness and response.” To be drafted rapidly by the INB of WHO Member States, the INB Bureau developed a Conceptual Zero Draft based on proposals from countries. In compiling initial proposals from member states, the INB Bureau has now developed a Bureau’s text to support the ongoing INB negotiations. This negotiating process seeks to culminate in the May 2024 World Health Assembly where the Pandemic Treaty could be adopted. This legal reform offers a unique opportunity to learn from human rights challenges in the COVID-19 response and establish human rights obligations to address future pandemics.

The Imperative for Human Rights in the Pandemic Treaty

The Pandemic Treaty provides a legal foundation to overcome human rights limitations exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic response led to wide-ranging human rights violations that impacted women and vulnerable populations, revealing inequities in global health governance and weakening the global health response. From the earliest days of the pandemic, WHO Director-General Tedros warned that “all countries must strike a fine balance between protecting health, minimizing economic and social disruption, and respecting human rights;” however, international guidance from global health and human rights institutions was often neglected in national responses, as seen where governments imposed discriminatory travel restrictions, digital contact-tracing violated individual privacy, and disease prevention measures limited access to underlying determinants of health.

Human rights challenges persisted through advances in COVID-19 vaccines, with the international community failing to meet international human rights obligations to fairly distribute medical countermeasures. Such violative actions impaired the pandemic response, with UN Secretary General Guterres decrying a continuing “pandemic of human rights abuses.” Learning from these human rights violations will be pivotal to building a world that is safer, fairer, and better prepared for future public health threats.

Human rights must therefore guide the Pandemic Treaty – through the participatory process of treaty negotiations, the substantive provisions in treaty obligations, and the institutional arrangements for treaty oversight. To develop a rights-based process for negotiating the Pandemic Treaty, full and meaningful civil society engagement – guided by the right to participation – is both required under international law and essential “to ensure a strong, transparent and legitimate process.”

Framing the substance of the Pandemic Treaty, human rights must be central to global health obligations, as the right to health provides a central normative foundation in preparing for and responding to pandemics. Beyond the right to health, human rights frame legal responsibilities in a public health emergency – establishing cross-cutting human rights principles, human rights underlying determinants of health, and obligations of an extraterritorial nature.

Finally, human rights must be incorporated into the accountability procedures established under the treaty, ensuring that treaty monitoring and review mechanisms assess the realization of human rights in global health.

Civil society has looked to these human rights obligations to guide WHO Member States in the development of the Pandemic Treaty.

Human Rights Advocacy in INB Negotiations

Global health law reforms have the potential to strengthen the foundations of human rights in global health governance, and civil society advocates have sought to engage with these intergovernmental negotiations. Even before the World Health Assembly resolved to develop a Pandemic Treaty, advocates had already pushed States to safeguard human rights, fearing that human rights obligations could be “lost, diluted, or misconstrued” in policy reforms amid a public health emergency.

Where the IPPPR neglected human rights recommendations in its final report on the COVID-19 response, advocates called on Member States to recognize the linkages between public health and human rights – both in amending the IHR and in developing new policies. With the decision to develop a Pandemic Treaty galvanizing new advocacy networks, global health advocates and human rights defenders came together in a Civil Society Alliance for Human Rights in the Pandemic Treaty (CSA).

To ensure civil society participation to advance human rights in the pandemic treaty negotiations, the CSA first sought to frame INB debates through the December 2021 development of “Ten Human Rights Principles for a Pandemic Treaty,” delineating human rights norms to be considered in the new treaty.

Civil society has since sought to engage with the INB drafting of the Pandemic Treaty, but has faced institutional challenges to meaningful participation. Drawing from longstanding practices of civil society participation in other international treaty drafting processes, civil society representatives have remained continuously involved in INB meeting sessions – participating in open meetings, engaging in technical intersessional work, and providing written feedback on working drafts.

Yet, formal participation in official proceedings has often proven impossible, as only nongovernmental organizations in official relations with WHO have been permitted to observe discussions and make limited interventions during INB meetings. While WHO has applauded the engagement of civil society in INB negotiations, UN human rights experts have expressed concerns about circumscribed opportunities for civil society.

Civil society advocates have themselves lamented the illusory nature of WHO engagement, with the INB providing opportunities for civil society statements at the margins of meetings but not looking to that input in Member State negotiations. Without full and meaningful participation of civil society, the Pandemic Treaty could lose valuable expertise from local contexts, key constituencies to support treaty adoption, and critical human rights lessons from the COVID-19 response.

This civil society advocacy has sought to support efforts to mainstream human rights standards in Pandemic Treaty obligations. Elaborating these human rights standards, the International Commission of Jurists and Global Health Law Consortium developed “Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights & Public Health Emergencies,” which clarify human rights applicable in public health emergencies and provide a basis for advancing human rights in the development of global health law.

In seeking to harmonize global health law and human rights law, ensuring “systemic integration” across legal regimes, the World Health Assembly resolution to develop a Pandemic Treaty, resulted in a series of specific human rights efforts to frame the substance of treaty provisions, with advocates looking to: (1) the right to health in maintaining core public health capacities, (2) rights-based public health practices in pandemic responses, (3) human rights principles for developing restrictive measures in emergency contexts, and (4) global solidarity in supporting international cooperation. This focus on international cooperation would become central to advocacy following the development of an effective vaccine, with State failures to ensure “vaccine equity” refocusing attention on WHO governance to strengthen human rights in the Pandemic Treaty.

Strengthening Human Rights in the Pandemic Treaty

The Pandemic Treaty provides a foundation to recognize international human rights law in the preamble and introductory sections and to mainstream international human rights norms and principles throughout the substantive obligations for public health prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery.

However, the Bureau’s text of the Pandemic Treaty largely reflects a step backward from the Zero Draft and past WHO advancements to ensure human rights obligations under global health law. Where international law recognizes that different bodies of international law should, as far as possible, be read to ensure their consistency with each other, these human rights setbacks across the Pandemic Treaty risk fragmenting international law, creating normative tensions across international legal regimes and undermining human rights in global health governance.

To harmonize human rights law and global health law, there is a need to revise the Pandemic Treaty to mainstream obligations relating to the (1) right to health, (2) rights-based approach to health, (3) permissibility of human rights restrictions to protect public health, and (4) imperative for international assistance and global solidarity.

RIGHT TO HEALTH

With “respect for human rights” recognized as a “general principle” (art. 3) in the introductory section, the right to health is specifically included as a guiding principle of the Pandemic Treaty (art. 2); however, the relationship between the right to health and Pandemic Treaty obligations is no longer clarified – with the Bureau text removing crucial provisions from the Conceptual Zero Draft:

(a) the central article on the “relationship with other international agreements and instruments” (including UN international human rights treaties),

(b) the legal foundations of the right to health (whether under the WHO Constitution or more recent human rights treaties and legal interpretations), and

(c) the entire article on the “protection of human rights.”

The Pandemic Treaty must recognize the centrality of the right to health in global health governance and the legal foundations of that right under international law. To strengthen human rights in global health, it will be necessary to detail the “right to the highest attainable standard of health” as a distinct “general principle” of the Pandemic Treaty (art. 3), with this provision providing a legal foundation to realize the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of health care and underlying determinants of health.

In upholding the wide-range of independent human rights supporting underlying determinants of health — recognizing the indivisibility, interconnectedness, and interrelatedness of all human rights — the “Whole-of-Government and Whole-of-Society Approaches” (art. 16) under the Pandemic Treaty must provide that national efforts ensure “the progressive realization of human rights obligations.”

Finally, where the Bureau’s text removed the article on the “protection of human rights” (A/INB/4/3, art. 14), this article should be reincorporated to prioritize human rights — recognizing that pandemic prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery “efforts shall be undertaken in accordance with human rights obligations” (14.1) and providing specific obligations to “prioritize protection and promotion of the right to health” during pandemics (14.2) — and expanded to uphold international legal obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health.

RIGHTS-BASED APPROACH TO PUBLIC HEALTH

Beyond the right to health, the human rights-based approach to health applies cross-cutting principles of human rights across public health policy, framing the ways in which the Pandemic Treaty can incorporate human rights obligations on:

(a) Non-Discrimination and Equality – expanding proscribed grounds of discrimination to match those under human rights law (including national origin and gender identity), integrating a gender perspective in health-related policies (prohibiting discrimination against women), and recognizing the synergistic effects of intersectionality (across inequalities).

(b) Participation – including provisions for meaningful civil society engagement in national and international regulatory strengthening, including the representation of vulnerable groups and opportunities for public mobilization (in political processes and regulatory authorities).

(c) Transparency – codifying a right to information as a basis to establish accessible and understandable pandemic information (recognizing underlying factors for health literacy and digital access) and openness and clarity of information (allowing individuals to take measures to protect themselves).

(d) Accountability – integrating human rights standards into international monitoring and review mechanisms (to assess the progressive realization of human rights) and guaranteeing opportunities for rights-holders to bring national claims for rights violations (and seek redress).

These principles can support INB amendments to the Bureau’s text to:

(a) Expand the General Principles (art. 3) related to equality – to consider the “structural challenges” that prevent “Equity” and reintroduce the separate principles (deleted in the Bureau text) on “gender equality” (including gender non-binary populations) and “non-discrimination and respect for diversity” (including intersectional discrimination).

(b) Establish civil society participation in International Collaboration and Cooperation (art. 15) – providing that governance mechanisms include “participation of affected persons and community-led organizations.”

(c) Ensure that efforts to strengthen Communication and Public Awareness (art. 17) increase public health literacy through “timely and equitable access to information on pandemics” (considering cultural barriers and digital divides) and government efforts to “address misinformation and disinformation” (through international cooperation).

(d) Provide that efforts to establish a peer-review monitoring mechanism under the Universal Health and Preparedness Review (art. 8) enhance human rights accountability by “considering recommendations provided by human rights monitoring mechanisms, especially in relation to the right to health.”

PERMISSIBILITY OF HUMAN RIGHTS RESTRICTIONS

There are clear standards under human rights law for permissible limitations of or derogations from human rights in times of emergency. With these standards elaborated in the context of public health emergencies, such human rights restrictions must be:

1. provided for and carried out in accordance with the law;

2. based on scientific principles and the best scientific, epidemiological, and other available evidence;

3. directed toward the legitimate objective of protecting public health;

4. strictly necessary in a democratic society;

5. the least intrusive and restrictive means available to protect public health;

6. neither arbitrary nor discriminatory in application;

7. of limited duration; and

8. subject to continuous, evidence-informed, and deliberative review and lifted as soon as such review no longer supports having these measures in place.

Where the Bureau’s text deleted previous recognition of human rights limitations and derogation standards in the Zero Draft (A/INB/4/3, art. 14), it is necessary to reintroduce and expand this draft provision, harmonize these restrictions with human rights guidelines, and align limitation and derogation standards between the Pandemic Treaty and amended IHR.

Furthering addressing these permissible limitations, the General Principles (art. 3) definition of “proportionality” should explicitly include reference to human rights limitations and should affirm that the application of proportionality exists alongside the principles of legality and necessity.

Finally, in considering the permissibility of these human rights limitations in specific contexts, the current discussions in the Pandemic Treaty remain silent on issues of “digital privacy” — posing risks to excessive surveillance, online discrimination, and intrusions into personal privacy — and additional reforms will be necessary to shape the proportionality of digital contact-tracing in future pandemic responses and ensure that such platforms do not inadvertently create new barriers to accessing health information and services.

INTERNATIONAL ASSISTANCE & GLOBAL SOLIDARITY

As international human rights law obligates states to take steps, through individual and collective action, towards the full realization of human rights, this obligation to cooperate in solidarity is not met in the Bureau text, which:

(a) provides options that could weaken “common but differentiated responsibilities” as a basis for international assistance under international human rights law,

(b) fails to recognize the insufficiency of the TRIPS Agreement (and Doha Declaration) in waiving intellectual property rights when necessary to realize access to medicines in a public health emergency, and

(c) ignores issues of trade imbalances, debt servicing, and financial sanctions (taken individually or through international forums) that prevent the procurement of essential countermeasures in a pandemic response.

Future revisions of the Pandemic Treaty must ensure (under art. 3) human rights obligations of “international assistance and cooperation,” including “extraterritorial obligations” under the right to health, looking to “individual and collective action” to promote human rights through “global solidarity” and framing “common but differentiated responsibilities” to provide greater support for states that bear the disproportionate burden of pandemic threats or lack adequate national health capacity.

Additionally, this focus on international assistance will require that human rights obligations be considered in the transfer of technology (art. 11), recognizing the inequities that underlie existing models of knowledge production, promoting investments in manufacturing capacity in the Global South, and prioritizing the right to health (and right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress) over intellectual property obligations by permitting States to “make use of the full flexibilities provided” in the TRIPS Agreement.

Finally, these extraterritorial human rights obligations must support sustainable finances and establish funding mechanisms for pandemic preparedness (art. 19) through the addition of obligations to “review and update debt servicing and tax agreements in order to enable countries to dedicate maximum available resources to health.”

IN CONCLUSION

Drawing from the collective trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pandemic Treaty provides new opportunities for strengthening human rights obligations under global health law, yet the early drafting process has exposed the threat that human rights could be abandoned in international efforts to protect public health. The coming months will determine the future of human rights in global health. Where health and human rights have long been seen as “inextricably linked,” the international obligations of human rights remain essential across the Pandemic Treaty – with universal obligations of human rights providing a common foundation for our collective response to future pandemic threats.

Get in touch with Benjamin Mason Meier at bmeier@unc.edu.

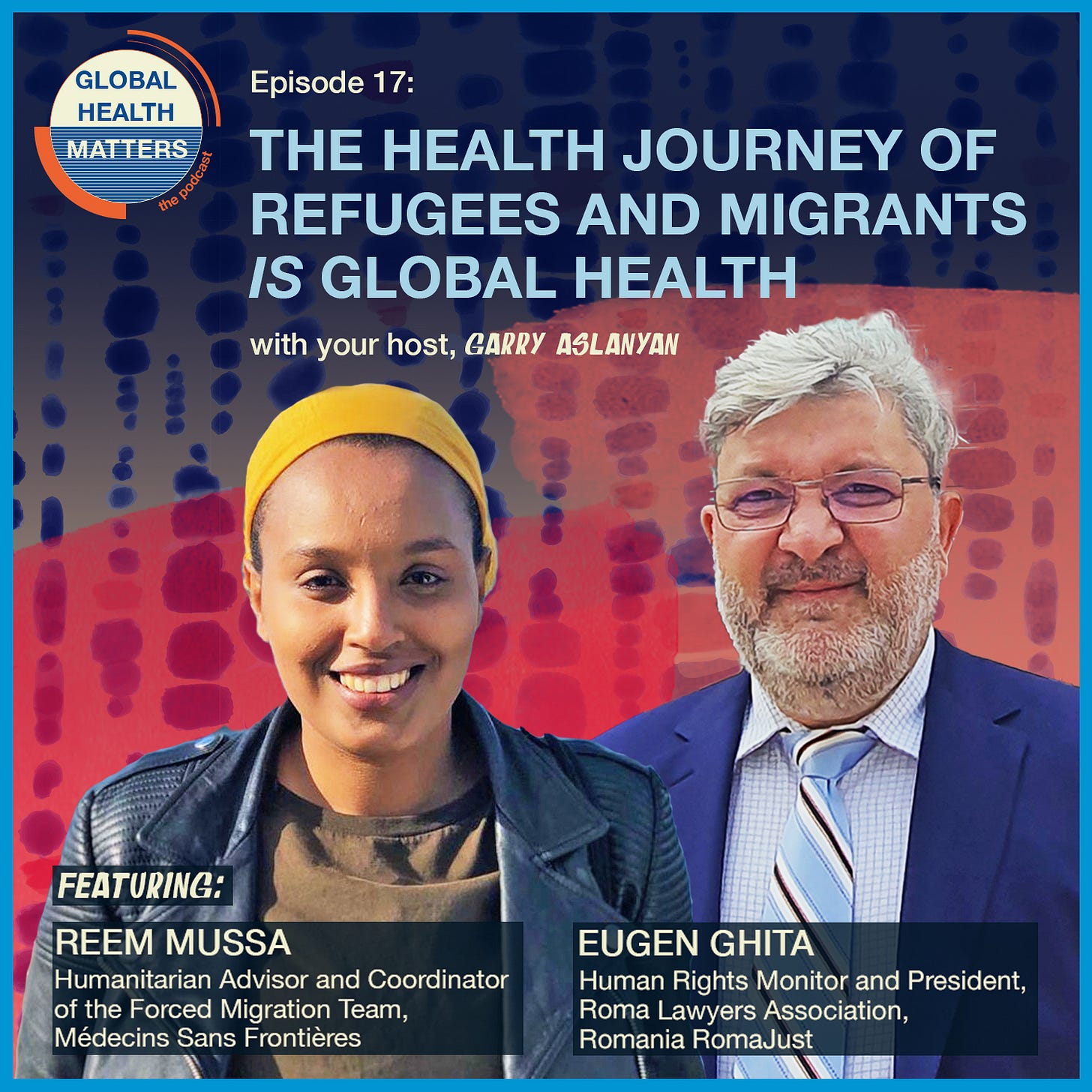

II. PODCAST CORNER

The health journey of refugees and migrants in global health

Here is a topic that rarely reaches the top of the global health agenda, that is the subject of the health of refugees and migrants. This podcast episode lays out the key issues for the listener and builds an awareness to ensure this topic gets better attention in the future.

Host Garry Aslanyan speaks with the following guests:

Eugen Ghiță: Human Rights Monitor and President, Roma Lawyers Association, Romania RomaJust

Reeem Mussa: Humanitarian Advisor and Coordinator of the Forced Migration Team, Médecins Sans Frontières

Listen to the episode.

Garry Aslanyan is the host and moderator of the Global Health Matters podcast. You can contact him at: aslanyang@who.int

This podcast promotion is sponsored by the Global Health Matters podcast.

If you wish to promote relevant information for readers of Geneva Health Files, for a modest fee, get in touch with us at patnaik.reporting@gmail.com.

III. WHAT WE ARE TRACKING:

Drafting Group Meeting: Intergovernmental Negotiating Body [12th-16th June]

Global health is everybody’s business. Help us probe the dynamics where science and politics interface with interests. Support investigative global health journalism.